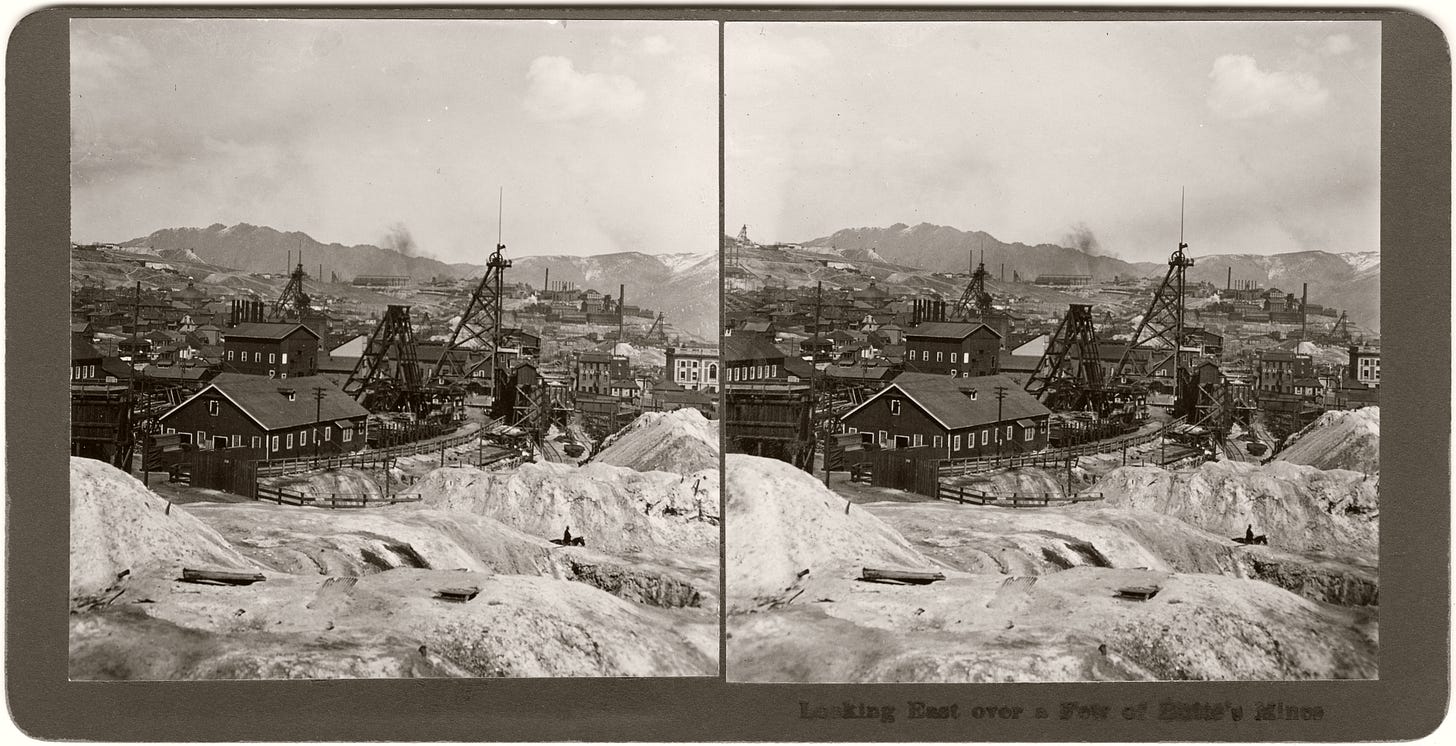

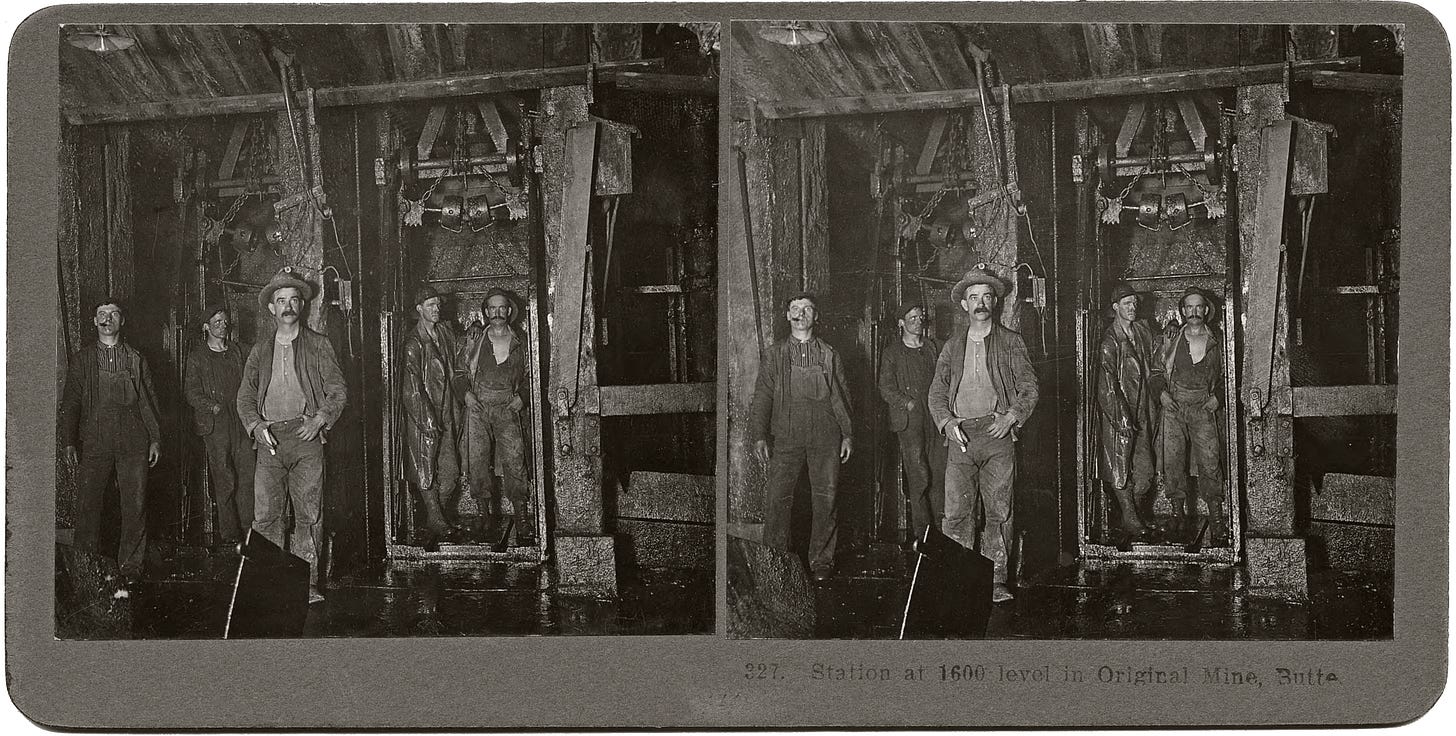

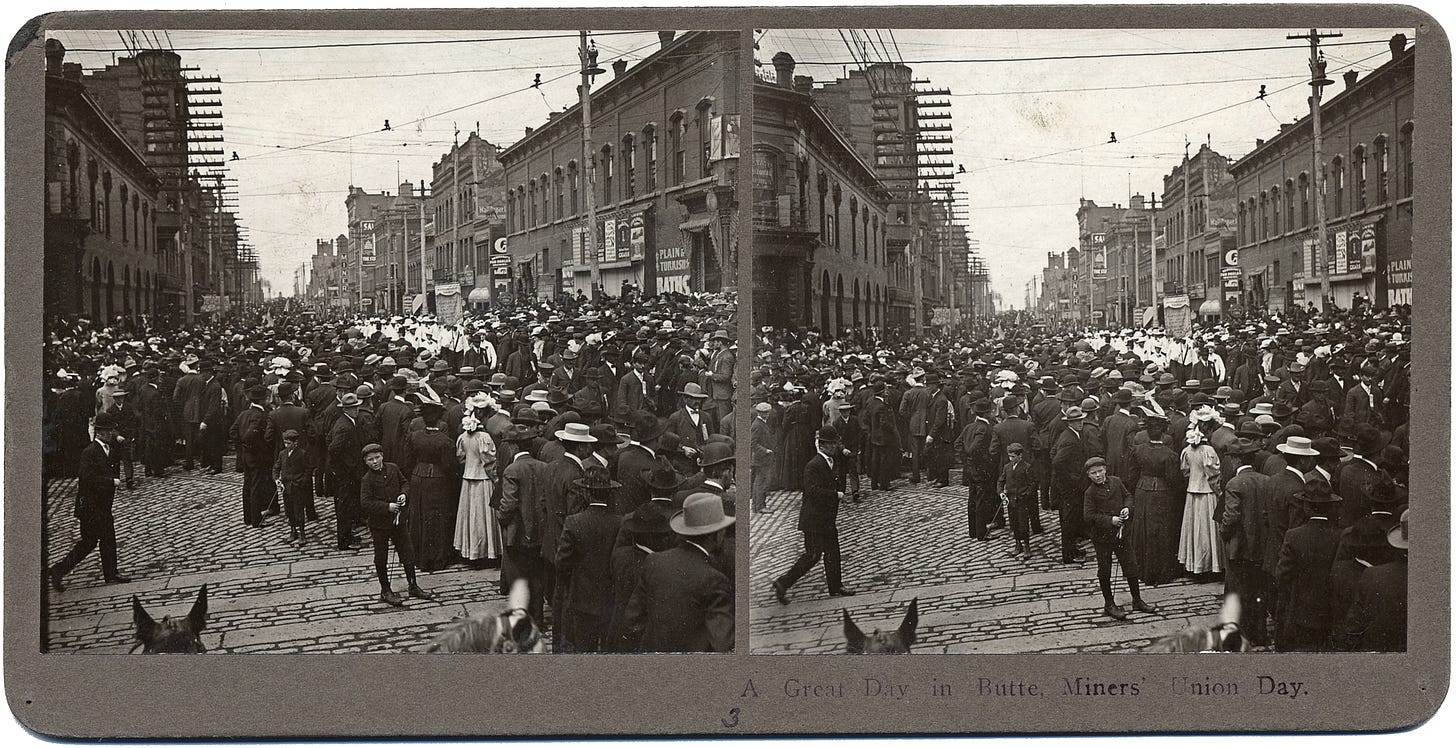

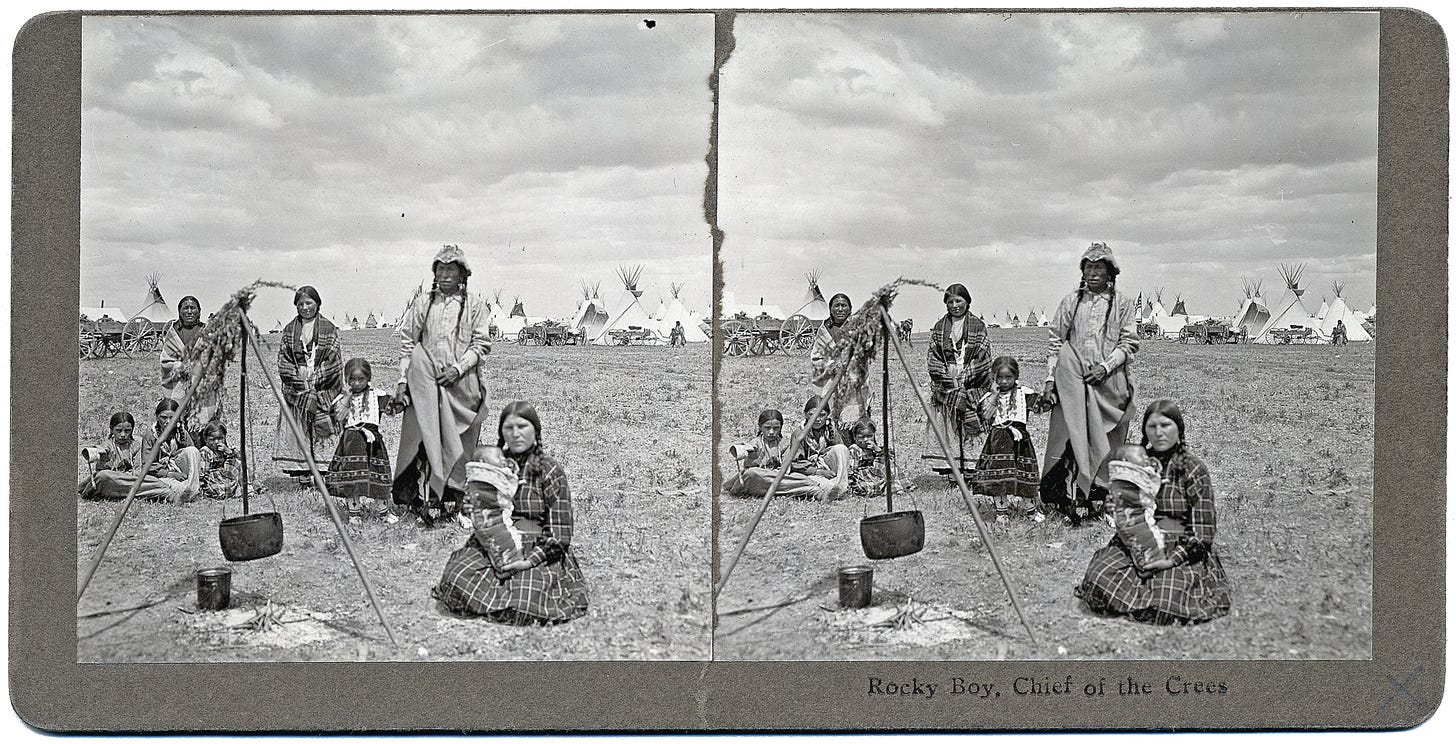

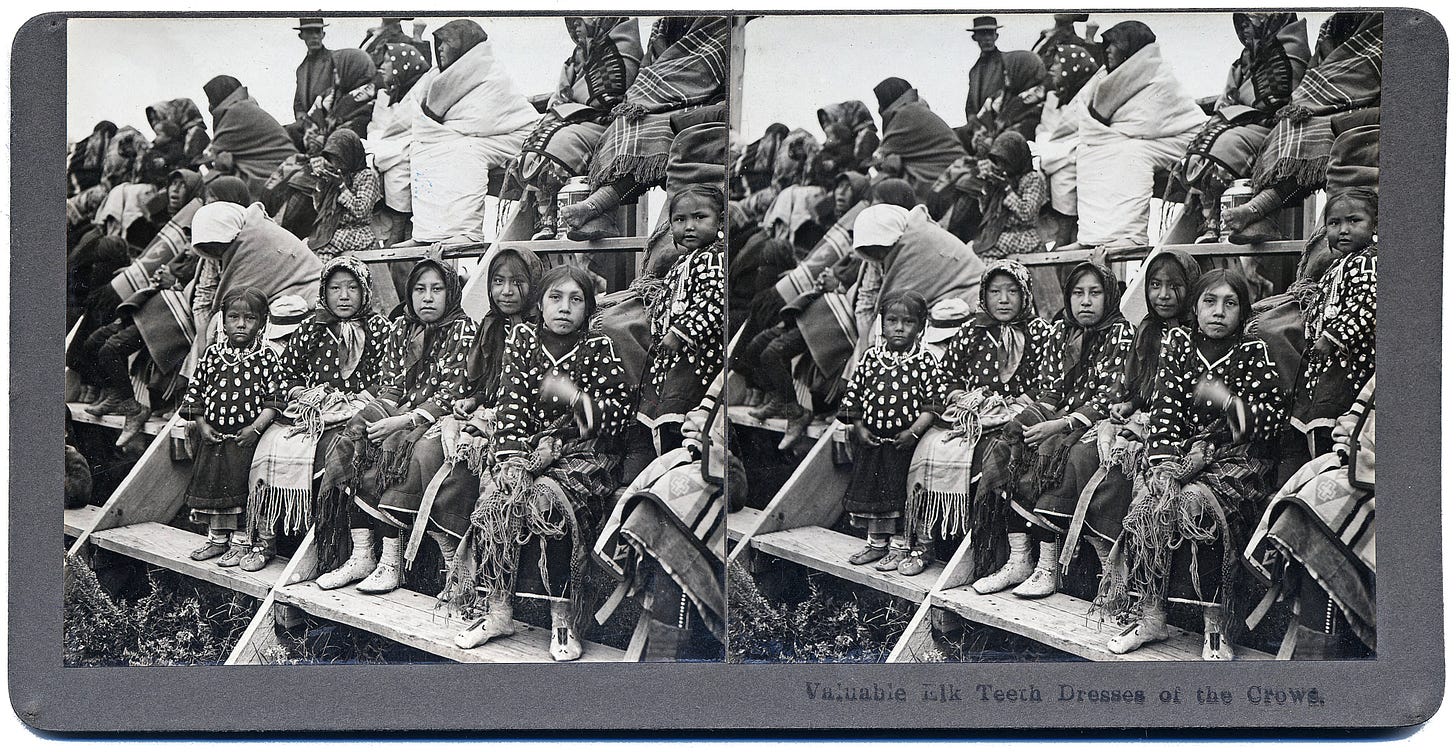

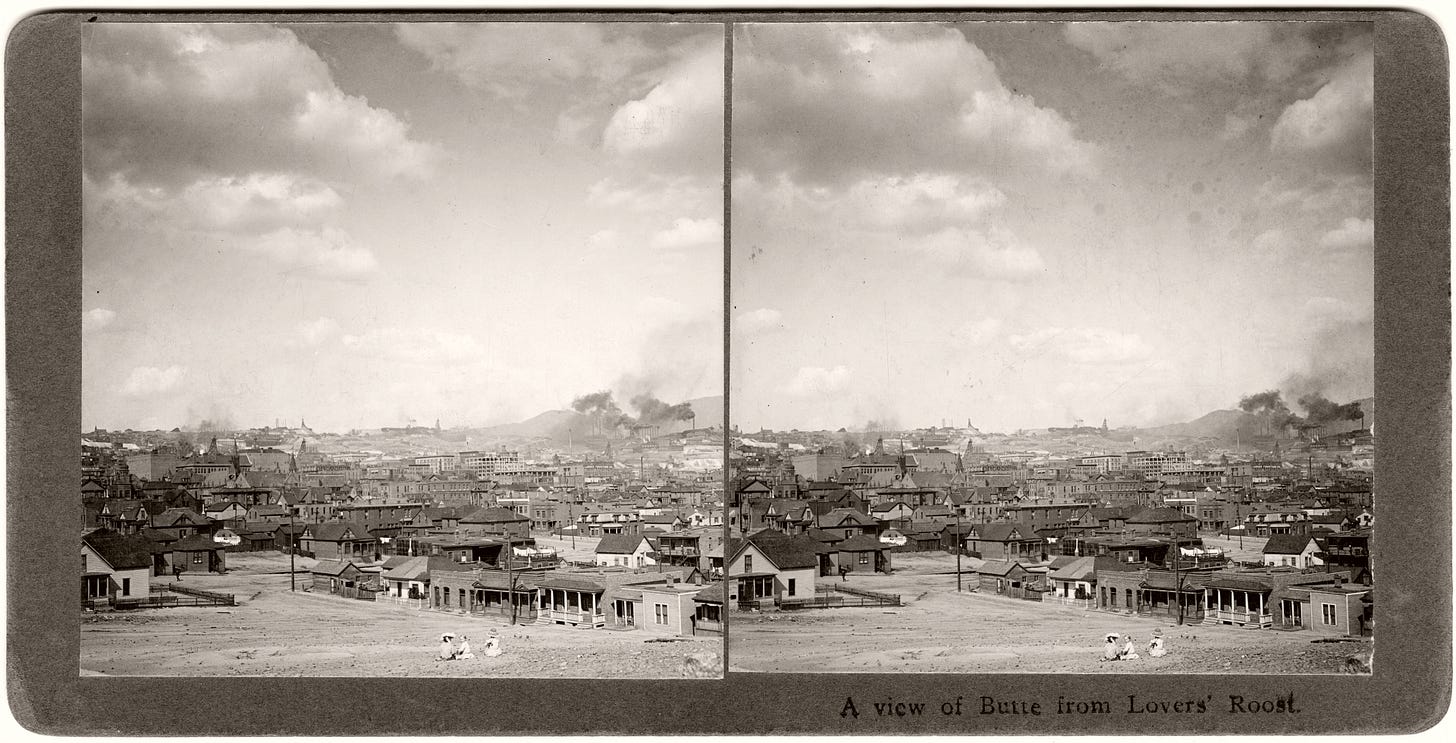

Based solely on his stereoscopic views of Butte taken between 1899 and 1912, Norman Arthur Forsyth deserves to be acknowledged as one of the most important western photographers of the early 20th century. His images of miners at work and children at play in the shadows of headframes and smelter stacks, of union parades, teeming streets and families in their finest at Columbia Gardens have become defining images of the city in its heyday. More than any other photographer of the time, Forsyth captured the cosmopolitanism and sophistication to which Butte aspired, and the scale of the industry which drove those aspirations.

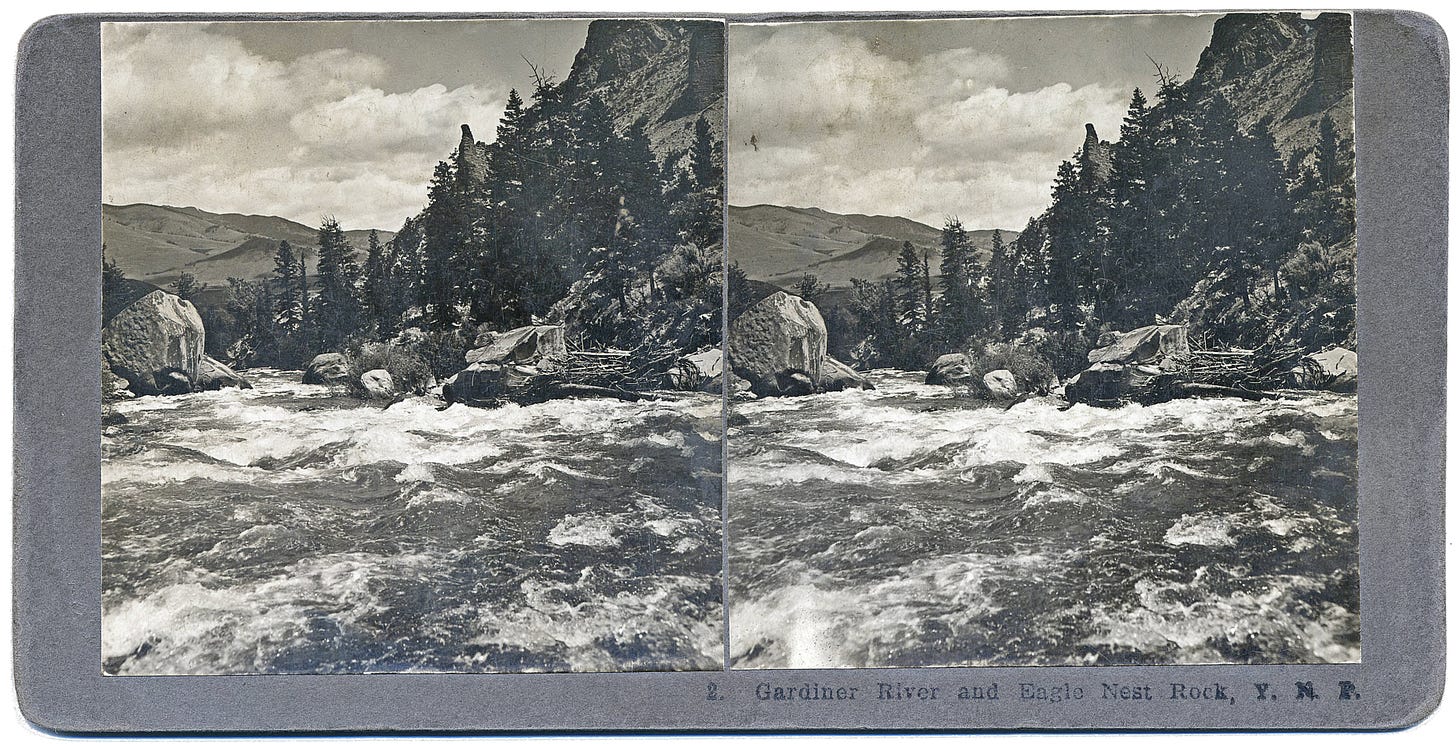

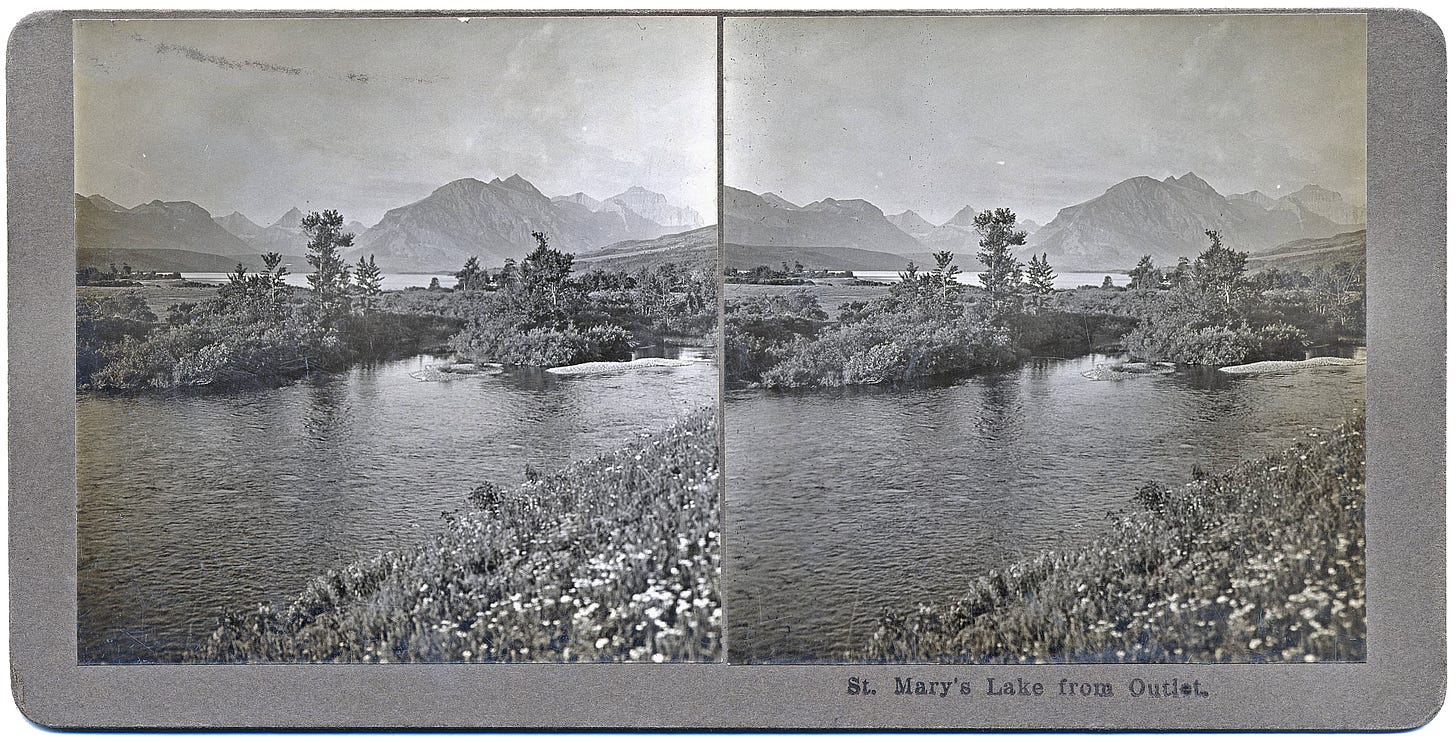

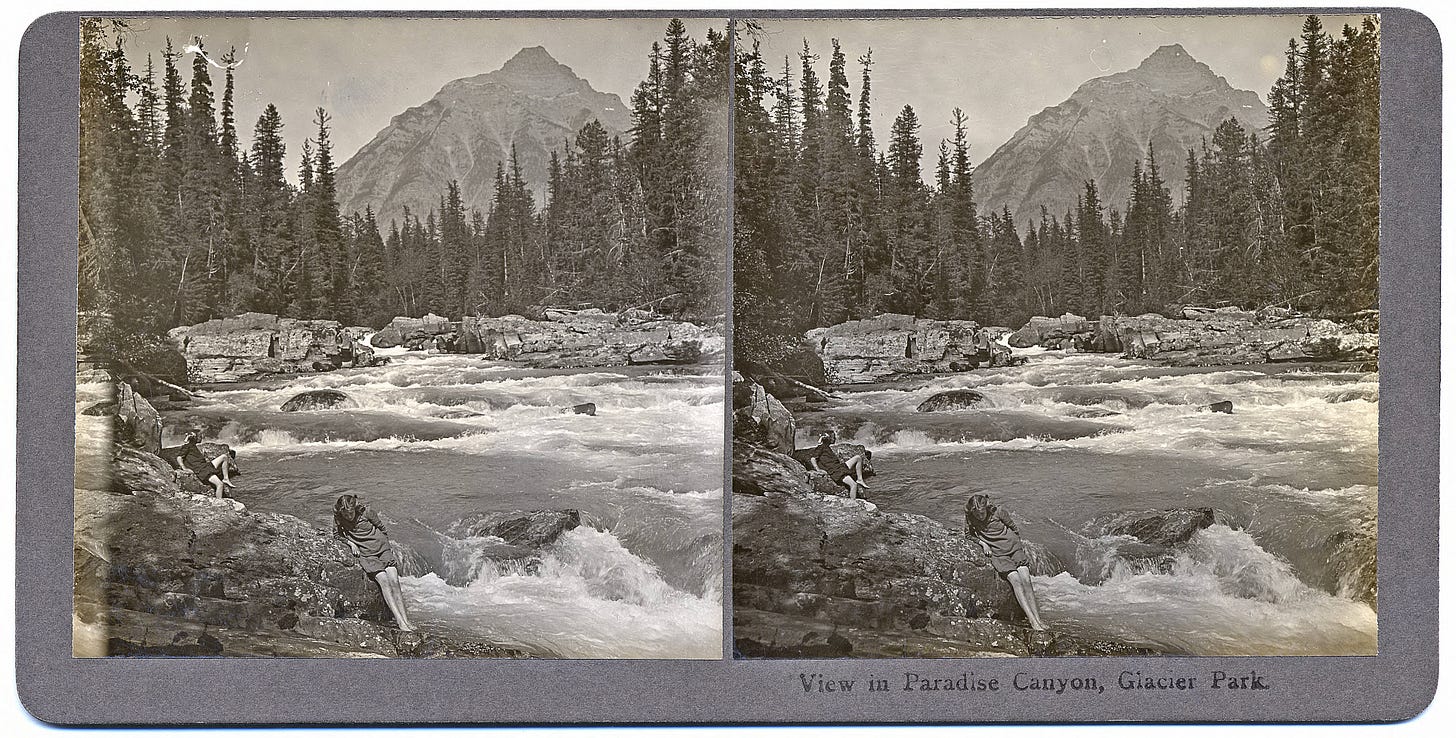

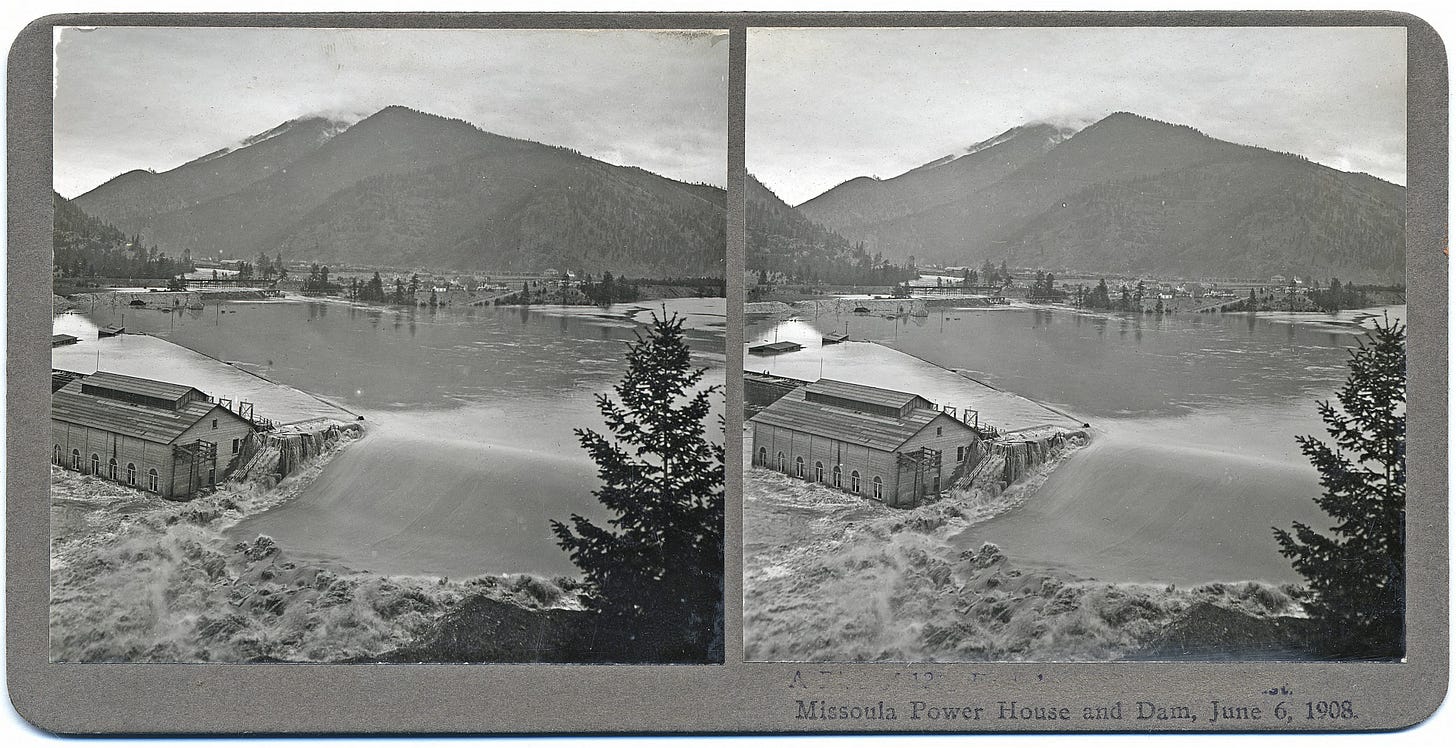

But these views account for only a fraction of Forsyth’s output during this period. Although officially based in Butte from 1903 to 1917, he traveled Montana extensively, as a tour guide and lecturer, as a canvasser for the Underwood & Underwood stereoscopic company, and as a photographer and publisher in his own right, documenting the state’s natural wonders and wildlife, its agriculture, burgeoning industry and indigenous peoples.

Today Forsyth’s “Through the Stereoscope” sets can reach thousands of dollars at auction, but at the time they never sold well, and he effectively abandoned photography in 1913 to focus on his work as a travel agent and salesman. However, in this relatively brief period Forsyth was prolific, creating a unique chronicle of Montana at the start of the 20th century. And yet even in Butte, the city he photographed so extensively, Forsyth remains largely unknown. While other photographers are lauded in books and exhibitions, he has been relegated to the footnotes and photo credits of others’ hagiographies.

This is partly a result of the fate of the medium in which he primarily worked. Today it is difficult to appreciate the enormous popularity of stereography in the 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1920s moving pictures had replaced stereographs in the public’s favor, and although the Keystone View Company continued to produce educational boxed sets for another three decades, almost all production had ceased by the 1950s. In the 21st century stereography is often seen as a Victorian curiosity. This is unfortunate. Forsyth’s views have been republished in countless books and journals in the hundred years since they were taken, and seen as such they remain historically significant photographs. But much of their artistic impact is lost in these reproductions; it is only when viewed through the stereoscope that we truly see them as the rich and immersive experiences Forsyth intended.

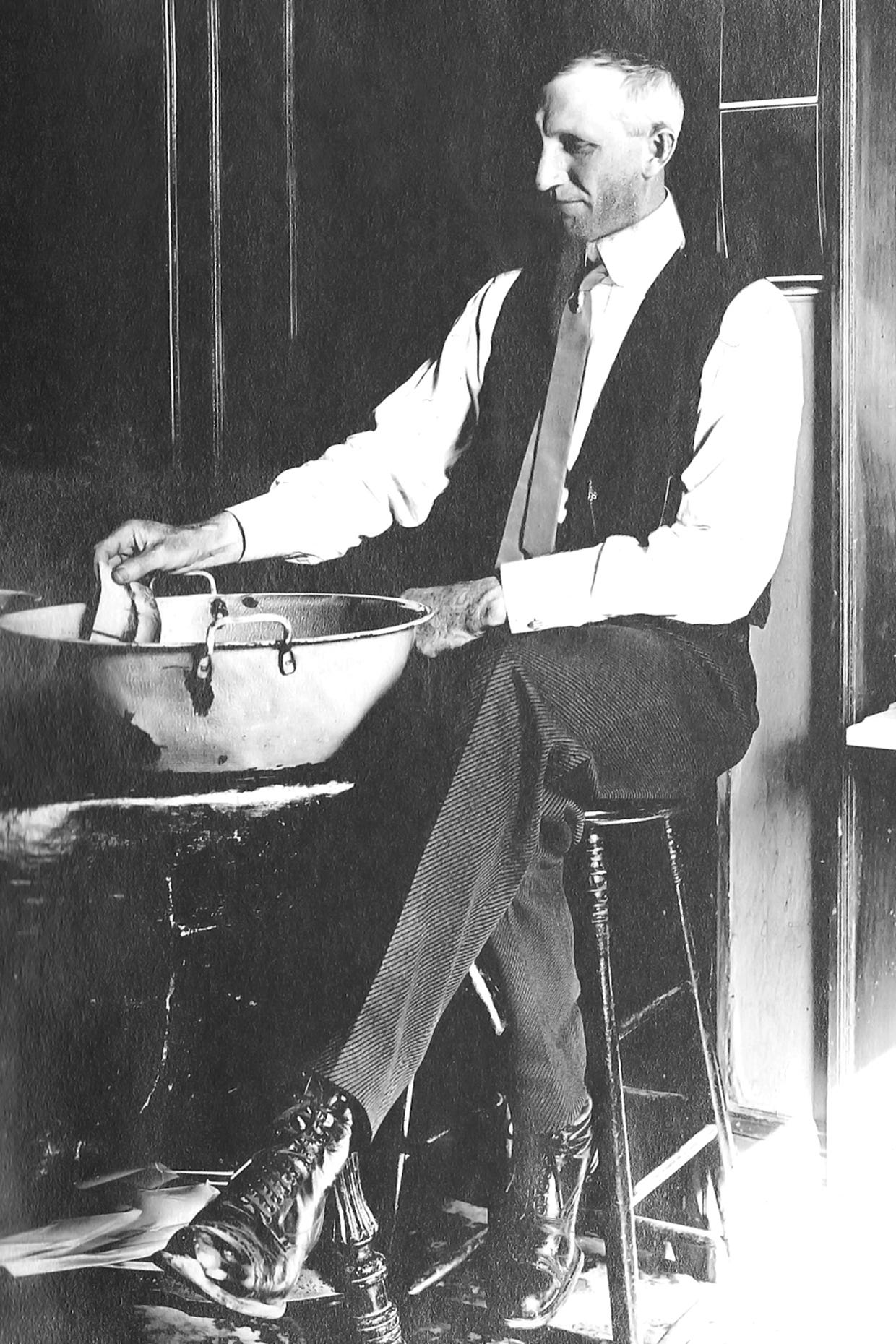

Forsyth’s relative obscurity can also be explained by a dearth of biographical information. Adopted as a child, he died unmarried and heirless aged 80. After shuttering his own stereographic business he spent three decades canvassing for Underwood & Underwood and the Keystone View Company, largely absent from city directories and census reports, staying in a succession of long-forgotten hotels and boarding houses or lodging with family and friends scattered across Montana, Wyoming and Nebraska. While this peripatetic lifestyle clearly suited him – he was still working for Keystone until illness finally forced him to retire at the age of 79 – he left the most nebulous of trails. But it is this trail I hope to illuminate, while providing an accurate timeline for his often vexingly undated stereoviews. Focusing on his years as a student at Wesleyan University in Lincoln, Nebraska, when his life seemed set to take a very different course, and on his time as a commercial photographer (1899-1912), I also hope to establish the case for a reevaluation of Forsyth’s contribution to the pictorial history of Montana.

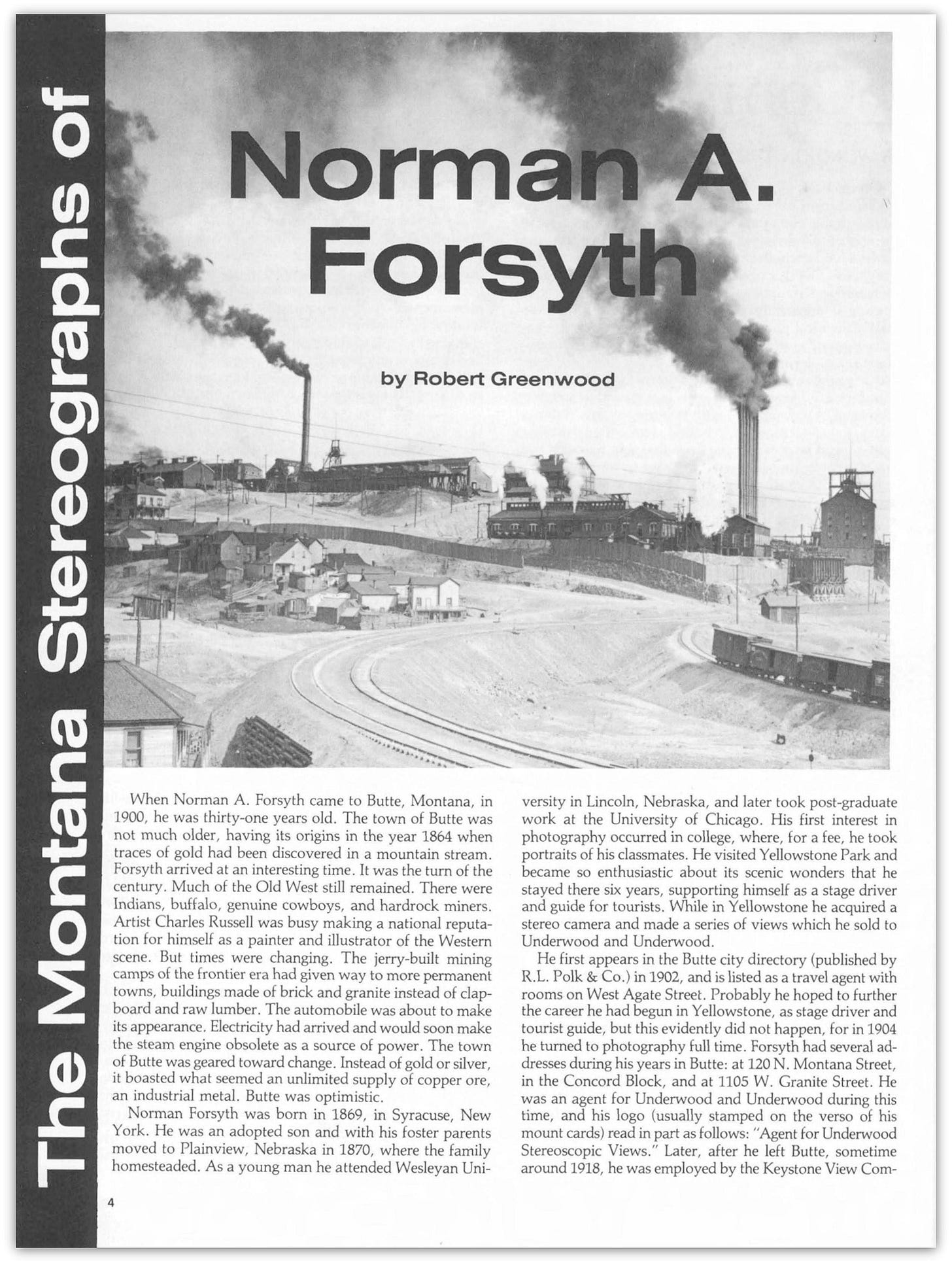

There is one notable exception to Forsyth’s elusiveness. Upon his death in Dillon in 1949, the Dillon Daily Tribune interviewed his close friend Wilber G. Squires,[1] who had known Forsyth since his childhood in Nebraska, and had followed him to Montana in 1917.[2] This interview is the only first-hand profile we have of Forsyth, and it would provide the biographical framework for two subsequent appraisals of his work. The first of these is Robert Greenwood’s “The Montana Stereographs of Norman A. Forsyth”, published in 1983 by the magazine of the National Stereoscopic Association. Befitting a somewhat specialist publication, the article focuses on the technical aspects of his work, offering little biographical information beyond that provided in the Tribune’s interview.

More substantial is Del Phillips’ self-published 1991 biography “Norman Forsyth: The Man and His Legacy”. In the course of his research Phillips interviewed several of Forsyth’s surviving family and friends, most notably the children of Wilber G. Squires. After moving to Montana the Squires became a second adoptive family to Forsyth, their home his home during those rare periods when he was not traveling. Alongside their personal recollections of growing up with the man they knew as “Uncle Normy”,[3] Genevieve Squires-Adair and Wilber L. Squires provided Phillips with numerous family photographs and artifacts.

Among these is a copy of a letter Forsyth wrote shortly before his death, addressed to a Mr. Hamilton. It appears from its content to be a letter to George E. Hamilton, co-manager of the Keystone View Company.[4] In it Forsyth primarily recalls his five decades working as an agent for Underwood & Underwood and Keystone, but it also includes a description of his discovery of stereography as a young boy, and his first years as a salesman while a student at Wesleyan Academy in Nebraska – a profoundly formative period in his life. These few brief paragraphs are the closest we have to a personal memoir, and as such the letter is invaluable, as is Del Phillips’ generosity with his sources. I am also indebted to Bill Hagerty of Arizona, whose grandparents Fred Peeso and Lillian Plint were friends and collaborators of Forsyth, and who has been unfailingly generous with his family’s mementos and memories.

Part 2: Earnest Young Christian (1869-1901).

[1] “Chats with Your Editor,” The Dillon Daily Tribune, Dillon, (MT), Dec. 19, 1949

[2] “Wilber G. Squires, Well Known Newsman, Dies,” The Independent Record, Helena, (MT), Nov. 16, 1959

[3] “Chats with Your Editor,” The Dillon Daily Tribune, Dillon, (MT), Dec. 19, 1949

[4] Letter from Forsyth to Mr. Hamilton, Jul. 30, 1949